Recent discussion around The Voice referendum revealed many misconceptions, not merely about Australia’s constitution and its relationship to our system of parliamentary governance, but the history and nature of Indigenous occupance.

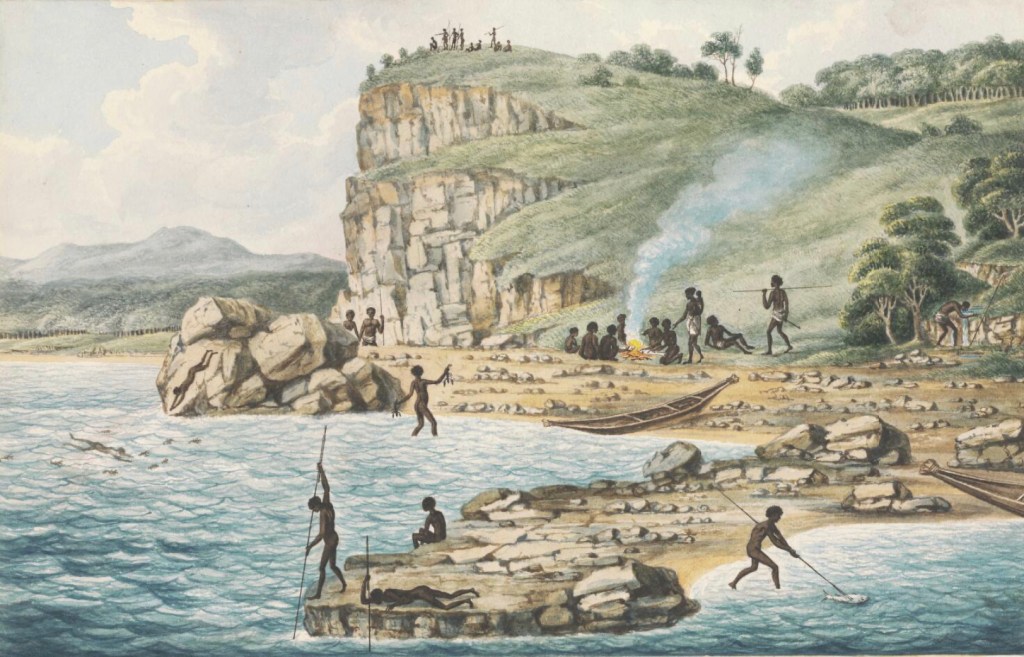

The term occupance refers to the inhabiting and modification of an area by humans. Closer examination of occupance reveals that it was far more localised and far less ecologically disturbing than what has been typically associated with the emergence of agriculture, namely large scale grain cultivation. It certainly required cooperation and astute ecological observation and understanding with a capacity to act in concert with the trophic levels in specific biogeographic regions.

Aboriginal people developed the first known techniques for grinding the edges of cutting tools as well as stone technology for grinding grass seeds for flour. Their stone tools were used to shape other tools, chop wood, and process animal skins.

Extensive stone fish traps were built along the Barka-Darling river at Brewarrina.

R. H. Mathews, presented the following work at the Proceedings of the Royal Society of NSW, on August 5, 1903

He observed:

The aboriginal builders collected large quantities of these stones and erected walls, in the way many of our farmers about Kiama used to build stone dykes or fences around their farms. These walls were erected in a substantial manner, being wider at the base, where also the larger stones were used, and tapering upward to

the top.

The stones were merely laid in position, without mortar or dressing of any kind, forming a structure sufficiently strong to resist the force of the current. The large stones used in the foundation or base of the wall were rolled into position, whilst the smaller ones were carried by the builders. Areas were enclosed in this manner, varying in dimensions from that of a small pond almost down to the size of a plunge bath, the walls of one enclosure being common to those around it, forming a labyrinth of inextricable windings. These enclosures were continued right across the channel from bank to bank, and occupied all the suitable portions of the river floor for about a quarter of a mile along its course. Some of the pens or traps were long and narrow, others nearly circular, whilst others were irregular in shape, according to the formation of the bed of the river, and the facilities for obtaining the heavy building material close at hand.

Budj Bim

In the Budj Bim area of south-west Victoria contains an extensiove system eel traps have been in use for over 6000 years. Budj Bim, is Gunditjmara country and has a volcanic landscape with numerous cultural features. In addition to the elaborate aquaculture system there are also remnants of ancient stone houses in village arrangements.

Occupance and the biophysical environment

Discussions around the voice referendum that I saw on social media revealed limited understandings of the brilliance of the ecological adaptations made by the indigenous people in Australia.

One aspect of indigenous settlement of Australia that has always fascinated me is the variety of adaptations made by language/clan groups, to the biogeography of the continent.

The map on the left reveals language/clan groups and on the right biogeographic regions. There is an obvious correlation between clusters of language/clan groups and biogeography.

Closer examination of Indigenous Australian occupance reveals that it was far more localised and far less ecologically disturbing than what has been typically associated with the emergence of agriculture, namely large scale grain cultivation. It certainly required cooperation and astute ecological observation and understanding with a capacity to act in concert with the trophic levels in specific biogeographic regions.

The Biggest Estate on Earth

In Bill Gammage’s work The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia Chapter 3 provides an account of the way Australian plants, animals, insects and bacteria have changed since 1788. He makes five observations;

Change 1: since 1788 compacted soil and speeding water have constricted water sources and the foods they nourished.

Change 2: in 1788 more water softened drought, spread resources, and let people walk easily over more of Australia. Even in arid regions they could expect to care for all their country, and think it’s plants and animals always sustainable.

Change 3: grass was widely available during Australia’s toughest season, offering management opportunities rare in Europe. Except in the wet people could burn grass at almost any time, knowing it would reshoot green. They could expect to attract grass eaters and their predators, especially in summer when today grass is scarce and animals stressed. This let them manage land not merely to help animals survive but to make them abundant, convenient and predictable.

Change 4: in 1788 trees, salt Bush and perennial grasses mitigated salinity; Now it is spreading.

Change 5: in 1788 people used almost every plant in some way. Losses since 1788 mask how widespread and connected resources were.

Gammage explains elsewhere that:

Two factors blended to entrench this, one ecological, the other religious. Ecologically, once you lay out country variably to suit all other species, you are committed to complex and long-term land management. Aboriginal religious philosophy explained and enforced this, chiefly via totems. All things were responsible for others of its totem and their habitats.

For example, emu people must care for emus and emu habitats, and emus must care for them. There was too a lesser but still strong responsibility to other totems and habitats, ensuring that all things were always under care.

Totems underwrote the ecological arrangement of Australia, creating an entire continent managed under the same Law for similar biodiverse purposes, no matter what the vegetation.

Despite vastly different plant communities,from spinifex to rainforest, from Tasmania to the Kimberleys, there were the same plant patterns – the same relationship between food or medicine plants and shelter plants.

Leave a reply to maximos62 Cancel reply