Through the night of 8 October 2015, Singapore had some drenching rain bringing temporary respite from the dense smoke haze that had hung over Singapore for the last few weeks. Rains over parts of Sumatra in particular, and a shift in local winds have brought clear skies and sunshine, yet the problem is by no means at an end. Fires still burned across Sumatra and Kalimantan.

On my way out to enjoy the respite and do a little shopping at Tekka Market, I struck up a conversation with one of the security personnel who work in my 30 story condominium. We often chat. She came from Pulau Bintan in Indonesia, around 40 kilometers away, and it’s another opportunity to speak Indonesian.

“When the air quality reaches 300 in Singapore people worry and many wear masks. In Kalimantan and Sumatra, it’s often much higher. It was about 1900 in Kalimantan last week,” she reminded me.

“Yes and over 500 in Palembang,” I added. “It’s climbing again here.”

“The smoke has blown north to Thailand and Vietnam, I heard it on the radio.”

“For the moment but it’s on the way up again here,” I said.

“It’s only moderate,” she replied.

“No it’s more than that already,” I said, reaching for my iPhone with the AQI app installed. “Here, look, PM2.5 is 148.”

That was two hours ago, now PM 2.5 is at an unhealthy 155. Comparing this with the inner Sydney station of Rozelle, close to my Australian home I see that by contrast, the Sydney station is at an AQI of 32.

The Indonesian situation

Thousands fled Pekanbaru, capital of Riau Province when the Pollutant Standards Index (PSI usually lower AQI as it doesn’t assign special status to PM2.5) hit a record 984 on 14 September.

People tried to make their way north to Medan in North Sumatra Province or over the mountain barrier to the west and into Western Sumatra’s capital Padang.

I often puzzle over just how things got so bad in Indonesia. The simple answer is that it’s taken a while and several factors are behind the disaster.

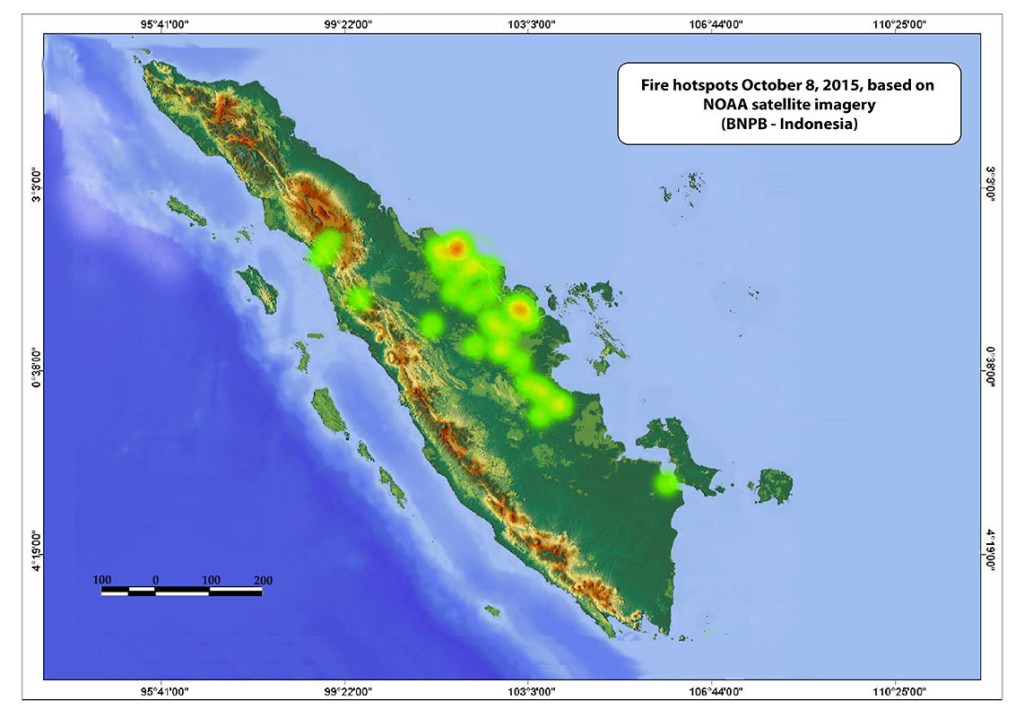

Yesterday, 8 October 2015, in Sumatra fire hotspots could easily be seen on satellite imagery from the Indonesian Disaster Mitigation Agency (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana – BNPB). This image was taken directly from the BNPB site.

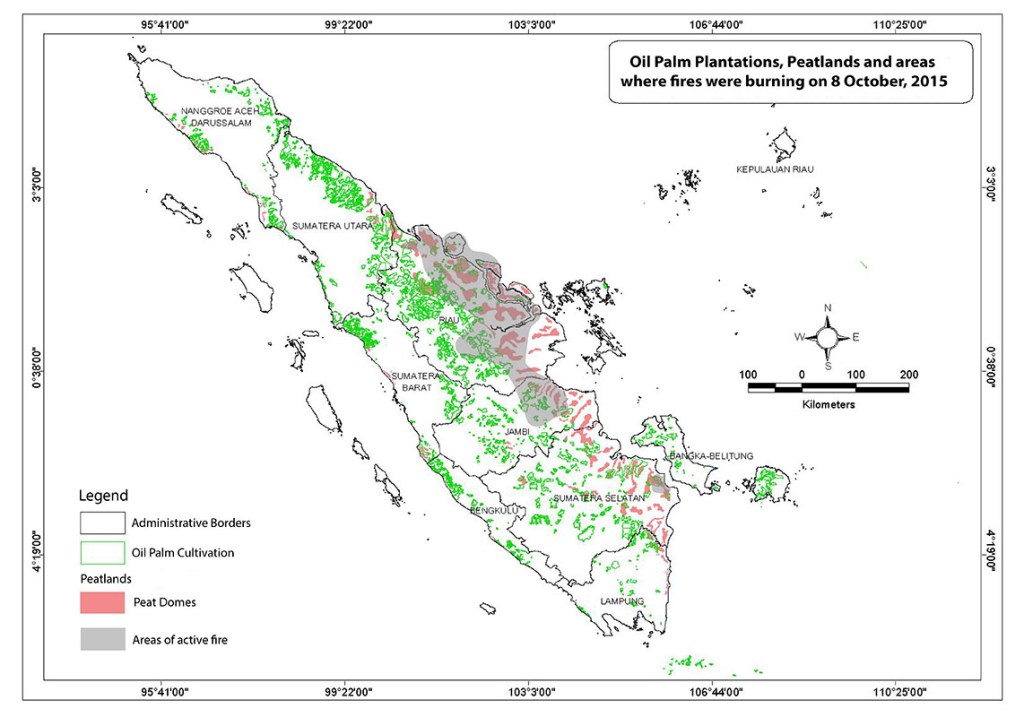

Overlaying the hotspot areas on a map of oil palm plantations and peatlands allows the extent of fires on peatlands to be easily seen. The provinces of Riau, Jambi and Sumatera Selatan all have fires burning on peatlands with the most intense fires on peatlands in Riau.

In my last post I quoted a reliable source indicating that at a global scale, CO2 emission from peatland drainage alone, in Southeast Asia, is contributing the equivalent of 1.3% to 3.1% of current global CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuel.

It is known that peatlands store about 58 kilograms of carbon in every cubic metre of peat. It is also clearly established that burning peatlands release carbon as CO2 at up to 500 times greater than the rate at which the carbon was sequestered. So why is this allowed to happen?

The demand for palm oil has increased

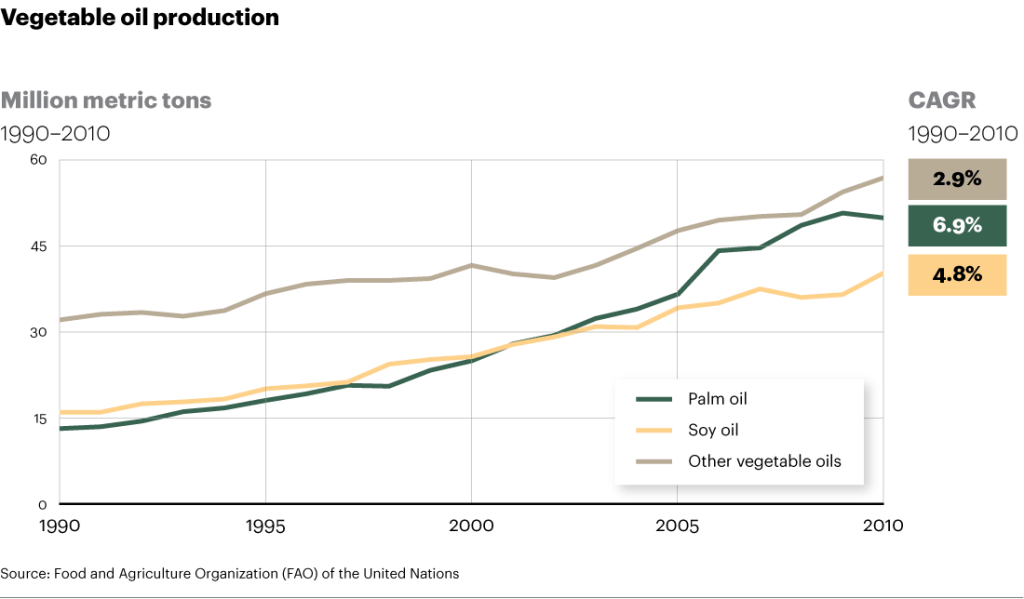

Land has long been planted with oil palms in Sumatra and the global demand for palm oil is growing. Palm oil is used in many things but its production depends on the plantation system of agriculture. It’s use worldwide from forest to finished product is well covered in the Guardian special on Palm Oil From rainforest to your cupboard: the real story of palm oil – interactive

The global increase in the demand for palm oil is plainly illustrated is the following graph.

Role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

In return for providing Indonesia with access to national development loans in the 1990s, the International Monetary Fund required the adoption Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP). In general, the SAP meant the implementation of “free market” programs and policy. Central to these programs were requirements for privatization and deregulation along with the reduction of trade barriers.

Unfortunately “free market’ solutions often tend to eschew a triple bottom line approach giving prominence to financial returns and neglecting social and environmental costs of production. This is starkly illustrated in the case of Indonesia’s palm oil industry.

The impact of SAPs on forests in Bolivia, Cameroon, and Indonesia

A UN Food and Agriculture Organisation report Considering the impact of structural adjustment policies on forests in Bolivia, Cameroon, and Indonesia, notes that Bolivia, Cameroon, and Indonesia all have between 40 and 60 percent of their land under tropical forest. In each of the three countries, the report observes, forest clearing and degradation has increased since adjustment. While this cannot be entirely attributed to the SAPs and most, if not all, the underlying trends already existed to some extent prior to their implementation, the SAPs seem to have been an important contributing factor.

SAPs had an impact of currency and led to currency devaluations. In Indonesia, the lower rupiah value has seen an increase in palm oil and rubber exports. Another factor was Indonesia maintaining its previously high level of road construction which, coupled with unclear land tenure has contributed to further deforestation.

Disaster Prevention

BNPB has an efficient capacity to identify and map problems using geospatial tools but it requires further access to high-resolution remotely sensed (satellite) imagery. Remaining unclear is the effectiveness of Indonesia’s firefighting response. Information about the extent of firefighting and prevention efforts is difficult to obtain.

On September 11, 2015, head of BNPB Willem Rampangilei announced that a deadline had been set to clear the haze created by the current fires and that 1,059the Indonesian military (TNI) personnel had been deployed to extinguish hotspots in Sumatra. Military Commander Gen. Gatot Nurmantyo also announced that an additional 1,150 personnel were ready for deployment if needed. He went on to advise that the military would target Musi Banyuasin, Banyuasin and Ogan Komering regencies in South Sumatra. No mention was made of Riau province where the highest concentration of hot spots was located.

On September 12, 2015, it was announced that Indonesia had declined an offer from Singapore to assist in fighting forest fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan.

Indonesian Environment and Forestry Minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar was reported as saying, in the Jakarta Post, that there are already 17 aircraft ready for water bombing and cloud seeding available in Indonesia and that there was a capacity to deploy an additional three planes adding that the aircraft were stationed in five provinces affected by forest fires.

Although Singapore made offers of further assistance, comprising a C-130 aircraft for cloud seeding operations, up to two C-130 aircraft to ferry a fire-fighting assistance team from the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF), a team from SCDF to provide assessment and planning assistance to their Indonesian counterparts in their firefighting efforts, high-resolution satellite pictures and hotspot coordinates and one Chinook helicopter with one SCDF water bucket for aerial firefighting, these were refused.

Minister Siti said, we rent Air Tractors from Australia. So I think [assistance] is not yet needed because our fleet is already numerous.

Overall the situation seems to suffer from lack of a coordinated response and insufficient quality contemporary data allowing interventions to be targeted most effectively.

Legal Responses within Indonesia

Legal responses to the smoke haze problem have been enacted at a variety of scales. Within Indonesia laws and regulations can apply at various levels of government

In Indonesia the levels of government are:

- Nasional – National

- Propinsi – Provincial

- Kabupaten – County

- Desa – Municipal and

- Dusun – Ward

During Suharto’s New Order regime deforestation took place within a highly centralised state. Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia has engaged in a process of devolution of powers to sub-national branches of government. Now the regulation of deforestation is taking place within a form of federal decentralisation. This devolution of powers and the accompanying legal and regulatory framework is known as Otonomi Daerah (Regional Autonomy) and shortened to Otda. It has important implications for any understanding of current deforestation in the country. According to Luke Lazarus Arnold in Deforestation in decentralised Indonesia: What’s the law got to do with it, Otda has involved devolution of significant amounts of political, administrative and fiscal authority to sub-national legislatures and executive governments – including over forestry.

Indonesia’s 1945 constitution Constitution states that ‘the land and the waters, as well as the natural riches therein, are to be controlled by the state to be exploited to the greatest benefit of the people’ This gave clear authority for the enacting of the 1967 Basic Forestry Law affirming that “all forest within the territory of the Republic of Indonesia… is to be controlled by the state”.

With the passing of new regional autonomy and fiscal laws in 2004, regional governors and assemblies received a greater share of power. Now the regions are empowered to exercise extensive autonomy over specific areas of governance which includes forestry, provided that their decisions maintain social welfare, public service, and regional competitiveness. Where matters are of a provincial nature the final authority rests with provincial government, districts/municipalities have jurisdiction over everything that is at that level alone. Clearly, this leaves space for much ambiguity as provincial, regional and district boundaries rarely accord with discrete bio-geographic regions. Many trans-boundary issues arise.

To make matters more complex, provinces can ‘delegate’ authority to districts/municipalities, and districts/ municipalities can delegate authority to villages. Authority over forestry can be so delegated.

So, to summarise things simply, great ambiguity remains over just which level of government has jurisdiction over many matters.

In 2005 Presidential Instruction 4/2005,13 called on all relevant government agencies to take firmer steps to enforce existing laws. Given the gravity of the deforestation and fire regime on peatlands, in particular, in a sense, this was an abrogation of national responsibility. This is not to say that efforts aren’t being made.

The image below is a statement of the legal situation pertaining to forest burning from the district (Kabupaten) of Bengkalis in Riau Province. The area is about 150 kilometers west of Singapore on the Straits of Malacca.

Bengkalis County Government,

Plantations and Forestry Department

BURNING FOREST FORBIDDEN

Law No. 41 of 1999 Forestry paragraph article

“each person is forbidden to burn forest”

By Threat of

15 (fifteen years) imprisonment and a maximum fine of

Rp. 5,000,000,000.00 ( five billion rupiah ) Article 78 paragraph ( 3 )

In this case, the laws applying are clearly County or Regency laws but the question remains, severe as they might be, whose task is it to enforce them? The police are not county police. Indonesia is also widely known for its corruption, Riau Province had, and probably still does have, an endemic corruption problem. In addition, there is already palm oil plantation development on Bengkalis peatlands and precious little forest cover remaining. Ironically, perhaps tragically, the sign stands on the margin of what appears to be cleared peatland.

Whatever the relevant legal framework applying the situation is complex and confusion arises our which laws might apply in any particular instance.

Legal Responses within the region

Just as riparian issues can be trans-boundary, having impacts in several countries and requiring international agreements to effectively regulate them, so too does the problem of trans-boundary haze.

ASEAN Agreement on Trans-boundary Haze Pollution

the ASEAN Agreement on Trans-boundary Haze Pollution on 10 June 2002. Indonesia ratified this agreement in September 2014.

Singapore Trans-boundary Haze Pollution Act 2014

Haze is now a recognised problem in South East Asia. In 2014 Singapore passed the Trans-boundary Haze Pollution Act in 2014. Companies found responsible for the smoke haze that affects Singapore and that are already listed on Singapore’s stock exchange can be financially penalised. Ten of the ASEAN members have also signed.

Indonesia blocks stricter enforcement

Recently Singapore also called for stricter enforcement against the perpetrators and the identification of those responsible for the haze in order to facilitate appropriate action. During a meeting in Jakarta in late July 2015, environment ministers from five ASEAN nations, including Indonesia, agreed to share information on a government-to-government basis that would help identify plantation companies on whose land fires start and cause haze.

Singapore has repeatedly urged Indonesia to publicly share maps on agricultural concessions owned by oil palm, timber and other commodity companies, which are often blamed for starting the fires, particularly in neighboring Sumatra. The Indonesian government, however, has refused to comply, with Minister Siti saying that Indonesian laws prevent the government from sharing concession maps.

Dr Nur Masripatin, director-general of climate change at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, told The Straits Times. Disclosing whose concession a certain hot spot is in would amount to disclosing a concession map. He added That is classified information. The government cannot do that. Dr Nur is in charge of overseeing efforts to contain forest and land fire and reports to Environment and Forestry Minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar.

Eventually, Minister Siti did agree to share the names of companies suspected of causing the fires when they are confirmed.

Despite the reluctance of Indonesia to divulge information on specific companies reports suggest that in Indonesia around 100 people and 15 companies are being investigated.

A failure to adequately assess the costs

Some suggest that the returns a price on carbon might deliver to Indonesia if deforestation was stopped are insufficient to compensate for the income to be earned from exploiting forests. In The Economic Contribution of Indonesia’s Forest-Based Industries, International Trade Strategies Pty Ltd, trading as ITS Global argues that, “As has been demonstrated elsewhere, the opportunity cost for replacing forestry or agriculture is particularly high. One analysis posits a conservative net present value (NPV) from palm oil, for example at USD3340, compared with USD2200 for carbon sequestration at a generous price of USD10/tC, excluding transaction costs. A generous estimate of a NPV for timber felling within tropical forests yields USD4400. “

They go on to suggest that, “The proposition, then, that carbon ‘farming’ or payments for environmental services (such as carbon sequestration) could somehow offset or equate to the economic contribution of forestry is fanciful at best.”

While such conclusions might apply to established agriculture and some of the less exploitative sectors of forestry, they grossly underestimate the impact of externalities in the development of palm oil plantations of Sumatra’s peatlands. Some of these impacts with related costs include:

Health impact on populations

Levels of smoke haze pollution in Indonesia, particularly in areas with peatlands like Riau Province, Sumatra, has frequently entered the AQI Hazardous band through September and October 2015. This is having serious health effects, not just because of this year’s fires but an accumulative impact on people repeatedly exposed to toxic haze.

In an article titled the Potential health impacts associated with peat smoke: a review Hinwood and Rodriguez provide a thorough summary of the literature on health impacts.

They explain that peat smoke is a mixture of organic and elemental carbon, potassium and sulphur and other by-products of combustion. It comprises quantities of fine particles classified as PM10 (particle diameter < 10 µm) and PM2.5 (particles diameter < 2.5 µm) occur with PM2.5 being predominant. It also includes carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, aldehydes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other organic compounds. Additionally, there are hazardous substances released including polycyclic aromatics and dioxin-like compounds as well as methyl chloride, non-methane hydrocarbons, ethylene, volatile organic compounds (VOC), methyl bromide, benzene, polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons and oxygenated derivatives

Smoke from peat fires is associated with a variety of health effects. The PM10 and PM2.5 particles can be inhaled into the lungs.PM2.5 particles, in particular, cause lung irritation, damaging lung tissue and causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems. People with heart disease, like congestive heart disease, can experience chest pain, palpitations, and shortness of breath or fatigue following exposure to particulate matter.

The Straits Times reported on the case of Wahyuni, a 15yr old student from Jambi died on 11 September. We knew Wahyuni had a pre-existing heart condition,” said her mother, Ms Nuraini. “Her heart was weak but she never had breathing difficulty like this before.

People with lung conditions such as chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive lung disease, emphysema, and asthma may not be able to breathe as deeply or efficiently as usual, and they may experience coughing, phlegm, chest discomfort, wheezing and shortness of breath.

Carbon monoxide (CO), a common component of peat fire smoke can pose health hazards at high concentrations and has been associated with increased respiratory and cardiovascular mortality. Health effects of exposure depend on concentrations. Common symptoms include headache, dizziness, weakness, nausea, confusion, disorientation, and visual disturbances and in severe poisoning marked hypotension, lethal arrhythmias, and electrocardiographic changes. So, people with angina or heart disease, pregnant women, developing fetuses, and those who exercise outdoors are particularly sensitive to carbon monoxide pollution.

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is also present and is associated with a 300% in nonspecific chronic respiratory symptoms in children. Asthmatic children are susceptible to increased levels of SO2, even with background levels considered acceptable.

Clearly, the health impacts have many implications none the least of which is the increased costs to businesses in employee days lost owing to systemic effects. Such externalities can be more easily measured than many and must be considered when assessing the costs and benefits of the palm oil production process.

Subsidence of peatlands and their increasing vulnerability to sea level rise and flooding

Flooding in deltas and riparian lowlands is accelerated by the subsidence of peatlands. Subsidence commonly occurs when channels are cut through peatlands as part of the clearing process. Peat dries out begins to release sequestered CO2 and shrinks. This is well documented in the Straits Times article which reminds us that unrestrained forest clearance to develop oil palm and pulpwood plantations leads to land subsidence.

The article observes that:

Millions of hectares of Indonesia’s former forest lands are slowly subsiding and could become flooded wastelands unable to grow food or timber-based products in one of the world’s most populous nations. Combined with rising sea levels, the scale of the problem becomes even more stark because much of the east coast of Sumatra is just a few metres above sea level.

It quotes Wetlands International which claims that between 70 percent and 80 percent of Sumatra’s peatlands have been drained, largely for agriculture.

Vast stretches of peatlands along Sumatra’s east coast that is mere metres above sea level. Mr. Marcel Silvius of Wetlands International tells us:

“These peatlands will become unproductive so that, over time, almost the entire east coast of Sumatra will consist of unproductive land that will become frequently flooded,” adding that this “means the livelihoods of the local communities will be jeopardised,” and ” industrial plantations will not be possible anymore.”

Remediation is unlikely to be an option so the costs associated with this aspect of the palm oil industry are huge and inter-generational.

Siltation of drainage basins, mangroves, and coastal waters

Clearing any land in humid environments increases runoff and reduces the percolation of water into soils. Run-off velocity in such situations also increases and without the protective forest layer erosion increases, topsoil is lost and carried into water courses, streams, and rivers. This, in turn, reduces the efficiency of channel flow, increasing flooding and also leading to increased siltation of estuaries and coastal waters. Such siltation can disturb coastal mangroves and associated fish breeding areas. River transport, coastal fishing and coastal navigation all suffer.

Muhammad Lukman, in research towards his PhD, has identified elevated levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in riparian and coastal sediments. He suggests that his findings could be evidence of the effects of widespread, long-term and intense agricultural burnings along with the many forest/peat swamp fires that have frequently occurred in the past 20 years or so.

Some estimates of cost can be made in terms of the costs of flood mitigation and control measures, losses arising from flooding of agricultural land and settled areas, and the immediate impacts on navigation and fishing

Forced closure of schools and educational institutions;

On 25 September, as haze hovered above AQI 300 in Singapore, the city-state closed schools and kindergartens and distributed protective N95 masks. Levels of smoke haze pollution were far higher in Indonesia where schools had been closed in the previous month. In Malaysia, the government announced that schools would be closed in areas with an AQI over 200. Yet, on Monday 5 October 2015, Detik online reported that in Pekanbaru, capital of Riau Province in Sumatra advised that schools had been closed for more than a month owing to the smoke haze. Finally, the Department of National Education Pekanbaru forced students to go to school despite the smoke haze.

Closure of airports and disruption of airline schedules.

Flights have frequently been cancelled at Sultan Syarif Kasim II (SSK II) airport Pekanbaru, in Riau province with visibility down to between 300 to 600 metres in the area. Elsewhere Kuching International Airport (KIA) in Sarawak, Malaysia on was closed Sept. 10 with visibility down to some 400 metres. In Indonesia, poor visibility due to smoke disrupted flight schedules at Pinang Kampai Airport, Riau.

Losses sustained by the tourism industry and other business sectors

Reuters quoted Irvin Seah, DBS economist in Singapore, who said, In 1997, the level of pollution was not this severe, and noting that the tourism industry’s contribution to the economy was relatively smaller back then.

The Reuters report observes that Tourism makes up 6.4 percent of Malaysia’s economy and about 5 to 6 percent of Singapore’s and quotes an ANZ research report that says, in Singapore, Shopping, restaurants, bars and outdoor entertainment will all suffer during this hazy period.

Among the events disrupted or even cancelled due to the haze were the 2015 FINA Swimming World Cup in Singapore and the Kuala Lumpur Marathon in Malaysia.

While losses in tourism and ancillary sectors can be calculated there are increased costs to businesses across the board. Developing and implementing disaster relief plans for employees is one area that is immediately obvious, then there are the issues of work days lost owing to respiratory or cardiopulmonary illnesses, disruptions to supply chains and various other schedules of usual business activity. Finally, there is the matter of impacts on ventilation and air conditioning filtration systems particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

Impact on global warming

This was also broached in the previous post Forest Burning and haze in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. The precise impact of anyone burning event is difficult to judge, but the immense quantities of carbon stored in the peatlands of Indonesia is cause for concern. One estimate suggests that Indonesia’s 1997 fires released 810 to 2,670 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, the equivalent of 13 to 40 percent of the fossil fuels emitted worldwide that year.

In a report entitled ‘Indonesian haze: Why it’s everyone’s problem’ on 18 September, 2015, CNN observed that, it’s a persistent, annual problem that disrupts lives, costs the governments of Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia billions of dollars, and leaves millions of people at risk of respiratory and other diseases. The land that burns is extremely carbon rich, raising Indonesia’s contribution to climate change.

The CNN report also reminds us that in 2014 Indonesia was ranked the world’s sixth-worst emitter of greenhouse gasses.

The RSPO and achieving sustainable industry standards

Some efforts are being made within the industry to accredit sustainably produced palm oil. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) offers an accreditation system for palm oil. It aims to unite stakeholders from the palm oil industry to develop and implement global standards for sustainable palm oil. To date, this has only enjoyed modest success.

Perhaps one of the reasons for its limited success to date is that RSPO includes representation from NGOs, social organisations, banks and businesses involved in the palm oil trade along with growers, processors, traders and retailers. In all, it has about 2000 members, representing 40% of the palm oil industry, across all sectors of the supply chain. With such a diversity of stakeholders achieving consensus can mean agreement around the lowest common denominator. Progress is slow and companies can gain RSPO certification for specific areas of their operations and then be permitted a further three years to demonstrate expanding compliance over their entire operation.

Under these conditions, some ambiguity around what constitutes sustainably produced palm oil remains, also the market penetration of sustainable palm oil is still minimal. RSPO’s secretary-general Darrel Webber was quoted by the Guardian newspaper as saying. “Sustainable palm oil is still not a commodity; it’s a niche. We only have 15% of the [total palm oil] market”.

To make matters worse, nearly half (48.3%) of the 8.59m tonnes of certified palm oil produced over the last 12 months has failed to find a buyer. Instead, it was sold as conventional palm oil without a price premium. Under such conditions, producers are not clamouring to obtain certification.

Future Prospects

Research Investment Fellow, Dept Environment, Earth, and Ecosystems, The Open University and Associate Research Scientist, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Columbia University have conducted research on prevention of fires in Indonesia publishing Seasonal forecasting of fire over Kalimantan, Indonesia. In their work, they demonstrate that severe fire and haze events in Indonesia can generally be predicted months in advance using predictions of seasonal rainfall from the ECMWF System 4 coupled ocean-atmosphere model.

At a global level, much needs to be done in regulating the market for palm oil and developing effective standards for sustainable production as a condition of market entry. Regionally, the legal framework is in place but more could be done in accurately accounting for externalities so that an accurate effective bottom line analysis of the costs and benefits of palm oil production might be calculated. Within Indonesia, an effective triple bottom line assessments of the costs and benefits of palm oil production must be conducted. There is also a need for clarification of the legal changes necessary to ensure an effective ban on further peatland clearing and burning for expansion of the palm oil industry.

This is no longer merely an Indonesian or an ASEAN issue. The implications of peatland clearing and burning are global and require careful assessment as their contribution to global warming is undeniable.

Leave a comment