These stories are from in my published multimedia book which is best appreciated in the Apple Books format.

A Departure for Timor L’Este

A Blue Bird taxi arrived within minutes. Staying close to Ngurah Rai Airport afforded a stress-free connection with the early morning Timor L’Este flight.

“Selamat pagi, Pak,” I said, opening the back door and wedging my large bag against the passenger side seat.

Already standing beside the car, the driver said “Pagi, Pak.”

“Easier for me if the bag is on the seat. “

“No problems, Pak,” he replied as he slipped behind the wheel

Glancing at him, I asked “How are you, Pak”?

“Fine”, he answered.

“Ngurah Rai International terminal please.”

“Baiklah,” he answered.

His Melanesian appearance was unsurprising, a point for conversation. I reasoned he was from Flores or perhaps West Timor.

Conscious such questions are common in Indonesia, I queried, “How long have you been in Bali?”

“Fifteen years. I come after finish school.”

“Brave, coming all the way here. Are you from Flores or Timor?”

“From Timor Barat, Pak.”

“Was it easy to find work?”

“I work in construction, carry bricks, timber, sand, cement. I share room with friends from Timor. We go to church, so plenty talk about work. Easy to find. We help friends.”

“Ah! Helping each other, eh? Saling bantu membantu.”

“Correct,” he confirmed.

“Where are you from in Timor Barat”

“Atambua.”

Atambua! A trigger, releasing a turmoil of recollections: forced evacuations; summary executions; kidnapping; disappearances; rape; and, brutalisation of a people, because they voted for independence. Then images of Dili and machete-wielding militia chasing down their quarry, kicking and hacking; the recurring vision of BBC journalist Jonathan Head pursued and narrowly escaping. All crowded in.

December 6, 1975 – Jepara Room, Istana Merdeka – Jakarta.

Courtesy Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

Photo by David Hume Kennerly David Hume Kennerly,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On Saturday 6 December 1975 Indonesia’s President Suharto met US President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. In that meeting Suharto advised them, “Fretlin has declared its independence unilaterally. In consequence, other parties declared their intentions of integrating with Indonesia. Portugal reported the situation to the United Nations but did not extend recognition to Fretlin. Portugal however is unable to control the situation, if this continues it will prolong the suffering of the refugees and increase the instability in the area.”[1]

Ford querieded, “The four other parties have asked for integration?”

“Yes,” Suharto replied, adding, “It is now important to determine what we can do to establish peace and order for the present, and the future, in the interest of the security of the area and Indonesia. These are some of the considerations we are now contemplating, we want your understanding if we deem it necessary to take rapid or drastic action.”

It is plain from the conversation that Suharto sought US approval for an invasion of East Timor, yet the language is diplomatic and sanitised.

In an apparent distancing move Kissinger added, “You appreciate that the use of US made arms could create problems.”

He wasn’t asking a question but reminding Suharto the US needed to keep some distance from events.

Kissinger continued, “it depends on how we construe it whether it is in self-defence, or a foreign operation. It is important that whatever you do succeeds quickly, we would be able to influence the reaction in America if whatever happens, happens after we return, this way there would be less chance of people talking in an unauthorized way, the President will be back on Monday at 2:00pm Jakarta time. We understand your problem and the need to move quickly but I am saying that it would be better if it were done after we returned”

Concerned about the length of the operation, Ford asked, “Do you anticipate a long guerrilla war there?”

“There will probably be a small guerrilla war,” Suharto noted, observing, “the local kings are important, however, and they are on our side, the UDT represents former government officials and Fretlin represents former soldiers, they are infected the same as the Portuguese army with communism.”

Communism, the magic word then. If it is was communist it was evil. It didn’t matter how anyone felt, what state they were living in, or whether they had any substantive theoretical understanding of communism. If something could be labelled as communist the ‘free world’ was more likely to help eradicate it, or at least turn a blind eye to the violations of human rights perpetrated in the name of anti-communism.

Kissinger concluded his discussion with Suharto saying, “If you have made plans, we will do our best to keep everyone quiet until the President returns home.”

Once US assent was obtained there was no further need for diplomatic niceties. Suharto didn’t wait. Indonesian forces invaded East Timor on Sunday 7 December 1975.

Years of violence and oppression followed.

Dictatorships inevitably fall. Suharto’s Order Baru Order fell in 1998 ushering in the period of Reformasi, yet the oppression in East Timor remained.

Suharto’s successor Habibie conceded that the populace of East Timorese should be granted the right to vote on whether they remain part of Indonesia or not. Once the vote on independence was inevitable the terror began, an organised program of intimidation, and threats of dire consequences, an attempt to thwart voter registration. It failed. 24 years of resistance had steeled the people.

When the United Nations revealed a 78.5 percent vote for independence Indonesian trained and armed militias began an offensive, attacking and murdering independence supporters. In Suai hundreds took shelter from Laksaur militia violence at Nossa Senhora de Fatima Church. Here a combined militia and military assault led to the deaths of 200, including three priests. Instances of violence were numerous and widespread, a fact well documented by Indonesia’s Investigation into Human Rights Violations in East Timor (KTTP-HAM).

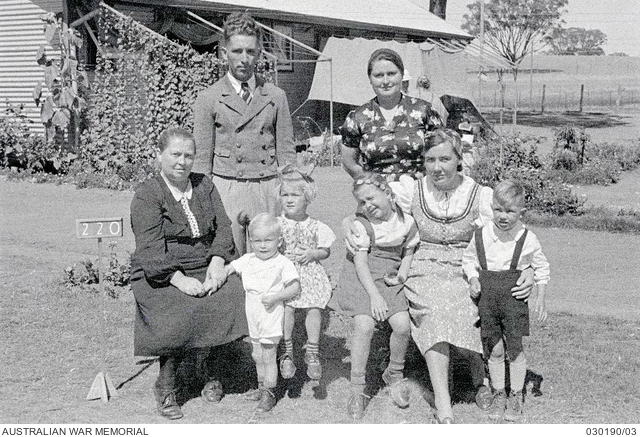

Finally, there were the deportations, about 250,000 forcibly relocated to places like Atambua. Stories of abuse, including sexual slavery, were widespread.

Despite the extreme oppression of the East Timorese, for me those years of violence culminated in powerful image of Jonathan in the evening news pursued by machete wielding pro-Indonesian militia. Having met Jonathan, deepened my shock

Perhaps Suharto and his generals envisaged the invasion as being carried out with stealth, but the daily television news cycle already ensured what might once have been done in relative darkness was soon before the eyes of the world. By the time of the vote anything taking place with television cameras in the vicinity would as likely as not appear on that day’s evening news. Herein lay Indonesia’s problem. The world was watching in a manner approaching real time.

When I finally spoke with Jonathan about the incident, he explained that day began peacefully, with a group of colleagues swimming off a sandy beach beneath Dili’s towering statue of Christ. Later at their base, a converted shop house rented to media crews by an enterprising Chinese businessman, word came that Dili’s United Nations headquarters was under attack. Piling into a Kijang, converted to accommodate his BBC team, they headed towards the UN compound. Tense crowds, people running, and several cracks of gunfire brought them to a standstill.

Jonathan recalled, “Up to that point almost all the gunfire we ever heard from any kind of militia attacks involved home-made guns that were not very accurate.”

“They were common,” I said, having seen numerous examples in otherwise peaceful parts of Indonesia .

“Then, we heard rather more gunfire and shouting. It was clear trouble was coming towards us, and some of the gunfire was not homemade guns. It was definitely automatic weapons fire. At that point we kind of stopped to take stock and looked at each other.”

My instinct would have been to make an unobtrusive retreat.

Jonathan confirmed this as the correct tactic given hindsight.

“After hostile environment training, I now know once there’s automatic weapons fire it’s time to just get the hell out,” he explained.

Of course then he hadn’t realised this.

He continued, “We sheltered down behind a breeze block building, just to stay out of sight and to reconsider what we did. Then three of our group made a run for the UN headquarters. They just belted in there shouting. We got film of it later.”

Very brave I thought, wondering whether I would have had the courage to make such a break for an obvious target with trouble converging.

“A BBC producer Jeremy and I delayed. The amount of gunfire we’d been hearing left us uncertain about putting ourselves out in the open. We were too slow.”

Referencing the story to his role as a reporter he added, “I was actually recording audio all the time. We could hear someone being attacked quite close to us, I’ve got the recording of it still, and you can hear the guy screaming, another colleague of mine, an Associated Press cameraman, was hiding in another house, he was out of sight and filmed them chopping this guy, who was killed. They chopped him down with a machete. You can hear him screaming, and then they were on to us, running fast, very strong, red eyed. So, they were either very drunk or possibly on methamphetamines. I felt from the behaviour they were very, very hyped up.”

“Ah! Methamphetamine!” Not mere alcohol if they were running with such strength, I reasoned.

“They slammed into us and grabbed hold of us yelling at us in Tetum, then in Indonesian, shouting, ‘Get out of here! Get out of here!’ ‘You guys are causing trouble.’ All the while they were panting, and they were bloody strong. We just did what you do instinctively. I actually let go of my tape recorder, he [one of the assailants] grabbed hold of it. We put our hands up to show we met no harm but there was no stopping them and we just broke and ran. Jeremy made a run for a cluster of banana trees in small village that was further away from the road. I didn’t, I wanted to get back to the main road because there were Indonesian police and an army post there too. So I started running in a different direction, but I got headed off when another couple of Militia guys came running up on my left, so I changed direction and started belting as fast as I could towards where Jeremy was, with these two groups of militias, about four guys in total, converging to cut me off. Then I tripped on a breeze block that was just lying on rough ground.”

“Oh no!” I blurted out, so gripped was I by the story.

He continued, “I was going so fast I went flat over on my face, and broke my elbow. I didn’t know at the time, and at that point the first guy chasing me had a machete and he just wacked me very hard and ran on but the next came up. He had an automatic weapon. I had my left arm up and he had two swings at me and first hit my arm very hard but a glancing blow. The second time he missed. As he was still swinging an Indonesian Intel military plainclothes officer arrived, I could hear him shouting as he ran across, Jangan bunuh wartawan!” Jonathan chuckled ironically.

“Don’t murder the journalist!” I repeated in English.

There was something macabrely funny about that. I was relieved Jonathan saw it as well, definitely a sign of healing.

Focusing again, he went on, “He got to this guy and held him off me and then went and got the other guy and pulled him back from where he had Jeremy. Then he pulled me up and took us back to the military post.”

Listening to his story my adrenaline level increased. I let out a deep breath of relief at his rescue.

“Obviously I was very shaken up,” he said. “I just laid into the Indonesians, saying “What the hell, why? You’re the army, you’re supposed to stop this. Why are you letting these guys do this? They are running havoc,” and they were all saying “Oh, we can’t interfere we don’t have that authority.

Maybe half an hour later, they brought over the militia guy who first attacked us. He was still panting, but they were calming him down. Then they explained to me that he was angry because some of his friends got killed. There had been a funeral, they were from the Aitarak militia. I think they had been at the funeral of the guys who died, that day, so they were pretty fired up.”

I glanced at the driver. Oblivious to my thoughts or condition he had calmly negotiated the airport traffic.

“Atambua, that’s right near the border with Timor L’Este?”

“Near border, yes,” he acknowledged

We pulled into the arrivals area. I stepped out, opened the rear door, grabbed my bag, waved away the porter, lent into the open passenger side door and paid the driver.

I smiled, “Keep the change.”

“Thank you, Sir. Safe journey to Dili.”

[1] The text of the Ford-Kissinger-Suharto discussion is documented in U.S. Embassy Jakarta Telegram 1579 to the Secretary State December 6, 1975. It is available from The National Security Archive. George Washington University. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB62/doc4.pdf

2017 I joined the Teachers for Timor (T4T) program. This meant I spent sometime in the town of Ainaro, south of Dili. My journey from Dili to Ainaro reminded me of the landscape I encountered as I drove through the Maritime Alps in Europe forty five years earlier. This mountainous area is a result of the collision of the African and Eurasian tectonic plates.

Along the road I became starkly aware of the massive tectonic forces operating between continents, forces that have uplifted the island of Timor producing this rugged landscape.

Local geology is complex; an unstable mix of clay rich marine sediments—a melange known as Bonbonaro scaly shales from the Miocene, sequentially overlain by deposits of Ainaro Gravels, relic river gravels from the Pliocene and Pleistocene eras. Uplift and tilting have jumbled the geology into an unstable mix of strata

Marine fossils are found through the mountains, even on the highest peaks. Timor L’Este’s forested ranges are honeycombed with caves, ideal terrain for a resistance movement.

A new era

Sometimes simple things can move slowly in Indonesia. Even after Suharto’s New Order regime fell, despite modernisation and efficiency bringing fresh standards of success, old ways could endure. At the Sriwijaya Airlines check-in counter there was one long line checking in passengers. Two other operators were absorbed in their work. One checked and re-checked details on the system, another waited on two passengers with overweight luggage. Both, a man and a woman, appeared to be from Timor L’Este.

“That bag is five kilos overweight and the other three over,” observed the operator. “The charge for the extra weight is 130,000 rupiah.”

“My hand luggage is light. Maybe I can move something there,” the woman suggested.

He rummaged through their large suitcase, and retrieved a hefty tome, a Portuguese-Indonesian dictionary. Laying it on the counter he said, “Yes, this book.”

He placed the suitcase on the scales again.

“Still four kilos over,” replied the check-in operator.

I’ve picked the wrong queue, I thought. Not alone, the line was growing behind me.

Watching the ponderous process resignation and not resistance engaged me. Recollections of that other time, the era of old the order once dubbed the ‘‘New Order’ intruded’. Lebaran, Idl Fitr, in Surabaya, computers down, staff making lists of passenger details on brown paper bags, a six hour wait in transit from Ujung Pandang.

Living through 15 years of ‘New Order’ rule in Indonesia meant caution, guarded most conversations. Only sometimes in private was it possible to speak one’s mind. The contrast with Australia where discourse was free and open was stark.

In Sydney I lived in a community with many academics, professionals and politically active people. In this milieu my efforts to establish a field study centre for Australian students, in Indonesia, were viewed with suspicion by some, and more so my frequent contact with Indonesian officialdom.

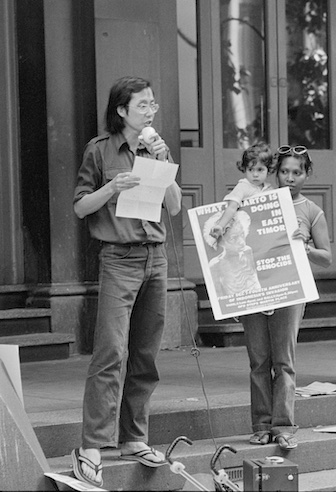

All major political parties avoided taking a critical stand on Indonesia’s invasion and annexation of the former Portuguese colony in East Timor. Only the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) still actively resisted Indonesian occupation.

A neighbour, Chris Elenor, had been part of a CPA group operating mobile radio contact with Fretilin. We often spoke, we talked about the technical aspects of setting up a transceiver in a remote area but for reasons of security he offered few operational details. Later he recounted his experience in an article Calling Fretilin. It described his first successful radio contact.

Amazing, through the crashing storm static, I could hear the tinny strains of Foho Ramelau[1]. This was it. Somehow, from somewhere, they were still broadcasting: “Viva Fretilin, Viva puovo Maubere.” Alarico Fernandes started his news bulletin. Deep breaths as I nervously caressed the microphone switch and waited to break in. He finished the first item. I hit the microphone button and the needle indicating signal strength soared strongly as I croaked out in as calm a voice as I could muster, “This is Kolibere, This is Kolibere. Calling Alarico Fernandes and Fretilin. This is Kolibere in Australia. Can you hear me, over.” No response, Alarico had continued with the next news item. I tried again and this time he stopped reading the bulletin, a short silence, he had heard something, who was it? I hit the airwaves again and this time, a response. “Hello Kolibere, Hello Kolibere, this is Alarico Fernandes. I am receiving you.” I pulled out the rapidly smudging paper with the frequencies, and radio schedules. They would need to listen at 10.30 am on any of three days and I would do the same on the other three. Were these schedules OK? He extravagantly confirmed the schedules and I then read him urgent messages from Jose Ramos Horta and Denis.[2]

A difficult period. Alliances changed throughout the struggle. In this early phase The National Council of Maubere Resistance acted as an umbrella group for organisations and individuals opposing Indonesian occupation. Fretilin was the dominant force.

Geographic and cultural diversity challenged efforts for a unified physical struggle, much less the formation of a unified platform of resistance and by October 1978 Alarico Fernandes was urging support for an operation he called ‘Skylight’. He wanted to remove most of the existing leadership of Fretilin.

This was not a simple struggle and conflict soon emerged between the revolutionary and moderate elements. By 1979, only 3 of the 52 members of Fretilin’s Central Committee survived. All others either died in battle, were captured or surrendered. Alarico Fernandes surrendered or was captured in late 1978. Radio Maubere stopped operating after this, and remained silent until 1985.

Martin Wesley Smith lived across the road from me during this low point in the struggle. He was always supportive of our efforts to educate young Australians about Indonesia.

I remembered him composing a piece for piano, percussion, tape & transparencies. He called it Kdadalak (For the Children of Timor). It was a powerful piece. It spoke directly to audiences, beyond words. Martin and his brother Rob were passionate about the plight of the East Timorese. Martin wrote of Kdadalak

Ultimately, though, for me to write powerful music I need to be powerfully inspired by something. Learning about the massacres of Timorese citizens, about a country denied its fundamental right of self-determination, about the plunder of Timorese possessions and resources, about my government’s complicity in the invasion and occupation of this ‘isle of fear’, and so on, was the inspiration I needed for a dozen or so Timor pieces over the next quarter of a century.[3]

His work was shown in Japan, the USA, Belgium, the Netherlands and France. He also produced a song dedicated to the five journalists killed in Balibo. He ans his brothers were leaders in the movement to support the Timorese people.

For me operating the field study centre, from 1983 onwards, required compromise. The radical within said I should be out protesting the injustice and the mass murder, while another voice urged me to use the skills I had and help prepare a generation who understood Indonesia was more than Suharto’s military dictatorship. Some my Australian neighbours and friends understood, I know Martin did. Amongst Indonesian friends and colleagues, I was forced to be someone entirely different. This challenged my sense of authenticity.

One notable low point was in 1985 when Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced recognition of Indonesian sovereignty over East Timor. Martin’s response was to compose Venceremos – We will Win.

Yet there were times when the breadth of opposition to the Indonesian annexation burst to the surface even under Suharto’s regime. On Tuesday, November 12, 1991, Indonesian troops killed up to 250 peaceful protesters in Dili’s Santa Cruz Cemetery, reactions were strong and global.

Attending a travel agent’s ‘educational’ in Sanur organised by Garuda Orient Holidays that night, an agent from Sydney approached me. “You know what has happened,” she said

“Not sure. What are you talking about?”

“There has been a massacre in Dili. It’s on BBC.”

“Goodness. No. The Indonesian military is relentless. There are some deeply disturbing things go on in this country.”

There was little else could be said.

Words of a former Australian diplomat came to mind, “The channels of darkness run deep in this country,” she said. Yet the converse was also true.

It was essential to be there, building networks and understanding in this huge country, confident that ultimately this authoritarian regime, dominated by military interests, must fall.

Finally, in 1995 came an opportunity to make another type of difference in producing a geography and history text, highlighting Australia’s links with Indonesia, it was to be used in Indonesian secondary schools. The Indonesian side vigorously resisted my account of the annexation of East Timor. We compromised, and the book was cleared for publication. Weeks before its soft launch, comprising a series of teacher workshops throughout Indonesia, the Suharto regime fell. Finally the chapter was re-written to convey a more authentic story.

Objects were shifted from suitcase to hand luggage and back. Finally he called to someone in another queue that had formed. “Joseph! Can you take these two books. We are still over weight?”

“No problem, Maun,” Joseph replied.

Check-in completed the queue moved forward. Boarding pass issued, hand luggage scanned, passport stamped, now enveloped in the retail realm of the departure longue. Without breakfast hunger triumphed, I bought a bar of chocolate and sipped a coffee.

The flight was called, more scanning, then onward to the plane. Boarding halted on the sky bridge welcoming yet another opportunity for reverie.

Was my volunteering to teach English for a month in Timor L’Este a form of penance after all that flying beneath the radar? Was it making amends for the failure to join others in more overt resistance to the invasion of this small country? Still pondering, a sudden move forward cued an answer. No it was valuable work. The struggle continues. That was just another phase.

The crowd parted as a man was helped from a wheel chair onto the plane. Aged by suffering, he moved with support on each arm. The line flowed once more.

Stepping into the plane I noticed the frail man seated in the first row, a younger man his companion.

Denpasar to Dili is a short hop. The weather was smooth. I settled into my seat. My fellow passenger was with the Timor L’Este Department of Fisheries. We chatted about illegal fishing in Exclusive Economic Zone. Soon he dosed off. I began typing notes on my earlier meeting with the driver from Atambua.

Later I moved to the forward toilet. It was occupied. Waiting, I yawned, then glanced at the younger man. “Sleepy,” I said, referring to myself.

“Yes, he just sleeps. His legs and abdomen are swollen. The doctor has sent him home,” the young man replied.

“You consulted a doctor in Indonesia?”

“In Denpasar.”

“At Sanglah hospital?”

“Yes, but there is nothing they can do.”

“What’s the problem?”

“Liver cancer.”

Such a candid response would be unusual in my own culture, but then I wouldn’t have asked. Palliative care seemed the only option. What could he expect in Timor L’Este?

“An expensive journey.”

“Yes, but the Ministry of Social Solidarity paid the fares and hospital costs, because it is beyond the capacity of our hospitals.”

“A fine program,” I replied.

This casual meeting underscored a broader reality. Disease recognises no political boundaries. Hepatitis B, a common precursor to liver cancer, remained endemic along the archipelago from Aceh to Papua. There was much shared historical and cultural experience, Suharto’s regime of tyranny being one tragic aspect.

Popping ears told me we would soon arrive, time to go back to my seat. This was shorter flight than I imagined.

[1] National anthem of the Timorese independence movement – Mount Ramelau.

[2] http://roughreds.com/rrone/elenor.html#4

[3] https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/drawing-inspiration-from-east-timor

A journey from Ainaro to Jakarta Dois

Directly ahead wildfire leapt up steep gullies towards Foho Madanaga’s towering prominence. Strong winds from Australia’s dry heart drove raging flames now lost in billowing white smoke. Intense combustion, and mere days after the dry season’s onset. The blaze presented no threat to my journey as the tilted bare rocky strata at the summit ensured certain extinction.

My mood was solemn as I walked up the rough gravel driveway from my homestay towards the main road bound for Jakarta Dois. My friend and colleague Philip first told me the Jakarta Dois story when he suggested I apply for Ballarat Grammar’s Teachers for Timor (T4T) project based in Ainaro.

“You speaking Bahasa Indonesia will be a big advantage.”

After Timor L’Este’s independence I was uncomfortable speaking Indonesian with its citizens. When teachers from Maliana visited Leichhardt Campus at Sydney Secondary College where I once taught, I asked if they minded me using the invader’s language. They had no problems with it, in fact they were happy we could communicate in a familiar language. They all studied Indonesian during the occupation.

“The Indonesian influences are obvious in Timor L’Este,” Philip continued. “It resembles Indonesia in many ways, but it’s a lot poorer.”

“I imagine it is.”

“When you’re there you must visit Jakarta Dois, or Jakarta Two.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s a place where many thousands of East Timorese were executed.”

“Really! When was that?”

“Over a period, from the beginning of the Indonesian military regime’s occupation of Timor L’Este in 1974 to 1999. Suspected opponents of the Indonesian regime, in Ainaro, were often arrested and told that they were being taken to Jakarta.”

“And this how it acquired the name Jakarta Dois?

“Yes. They weren’t taken to Jakarta, just to a spot about five kilometers south and thrown off a cliff. From what I’ve been told, some were shot first, others were tortured, and some even had their feet cut off at the ankles before being thrown over.”

I stepped from the driveway onto the road. Opposite, children and dogs played on the dusty verge. Such a typical scene in rural Timor L’Este. Several steps later amplified music announced a cavalcade’s approach. Motorbikes and tabletop trucks bedecked with National, Fretlin and Falintil flags raced by, a sign the negotiations over ministerial portfolios in the new Fretlin led coalition government had concluded.

Old habits linger in Timor-Leste. The cavalcade evoked images of a still assertive anti-colonial, almost revolutionary, spirit. In electoral terms it meant a preference for candidates associated with “Generation 75 revealing that for many the past was prominently in the present and shaping the political landscape. Many found it difficult to leave the past behind.

The cavalcade headed towards Jakarta Dois. I wondered how far they were going.

Weeks earlier I went to Jakarta Dois with colleagues, from the T4T program, I knew the route. An easy walk, it first wound through Ainaro’s outskirts, traversing ephemeral watercourses and hills, before entering a gradual descent between the Maumali and Sarai Rivers. Gun-barrel straight in parts, it was lined by a simple scattered house, stands of young teak trees, corn gardens, and patches of green leafy vegetables.

Jakarta Two is on a narrow ridge line. To its west cliffs running perilously close to the road drop 30 to 40 metres into the Sarai River valley. Local geology is complex, an unstable mix, clay rich marine sediments, a melange known as Bonbonaro scaly shales from the Miocene, sequentially overlain by deposits of Ainaro Gravels, relic river gravels from the Pliocene and Pleistocene eras. Uplift and tilting have jumbled the geology into an unstable mix of strata. Landslides and vertical cliff line retreat are common. On my first visit I was shocked at the undercutting eating into the road, pinned with steel supports in places to slow the erosion. It was far too dangerous to risk standing on the edge of the cliff.

There were survivors of this savagery. One story was recounted by a woman who had miraculously managed to latch onto a robust shrub or small tree that grew from the cliff line. She told how people around her had been thrown over and dashed on the rocks below. I imagined the twisted bodies and the groans of those who had not been instantly killed in slow agonising deaths.

Visions of corpses at the base of the cliff, denied their burial rites, their bodies wasting in the elements pierced my mind. I saw human forms degrading into a desiccated tortured tangle, a sight that intruded and recurred whenever I thought of this place.

Before my second visit I began researching Jakarta Dois, a testing task with the Internet speeds in Ainaro. I used East Timor independence campaigner, Rob Wesley-Smith, as a fixed point to launch my search. Rob’s writing pointed me to important observations by Max Stahl, a nom de plume, his real name is Christopher Wenner. He shot footage during the Santa Cruz cemetery massacre in Dili. In 1999 he returned to East Timor under the pseudonym Max Stahl and seemed to have gone straight to the Ainaro area.

Reading Wenner’s confirmed the accuracy of my visions. He found “a tangle of bodies, shrivelled under the hot sun, crumpled on the rocks. Their hands were tied behind their backs. The bare feet had been hacked off at the arch.”[1]

My purpose in making this second visit was to read the prayers for the departed to offer them words of peace and comfort, wherever they were.[2]

I expected to find traces of the pain this place must have witnessed. In my experience, acts of mass murder can leave an emanation of deep pain yet here on the brink of Jakarta Two I felt little. After offering my prayer I was content with the notion that prayers from countless others had brought peace to the precipice, a sense of spiritual calm. While some measure of moral outrage remained acrophobia and a sense of bewilderment were my dominant feelings. Yet something else was haunting me. The spirits of the departed were at rest but the land was not.

Across the valley the ridge line was largely treeless, its natural slope modified by clear signs of terracing, yet the entire area seemed unkempt. Erosive forces and mass wasting were plainly at work. Why weren’t the farmers caring for the land? I wondered there was something strange.

I began to look more widely. In numerous places there was evidence of once a thriving agriculture its fields now untended and wasting away. War, mass murder, starvation, and deportations had stripped the land of agricultural knowledge and labour. For me it felt as if the ghosts of farmers past stood mourning what once had been.

Later I found the writings of Mike Sandifor, Geology Professor at Melbourne University, who had also visited this place. He too noticed, “In many places the landscape was imbued with a dark shadow as testimony to the brutal rural depopulation that occurred under the Indonesian occupation in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s.”[3]

Students I spoke with in Ainaro had said little of these killings, but these numerous acts of mass murder had left a demographic scar. Starvation and neglect also accounted for many deaths. The country had a median age of less than 20 years with 62% of the population under 25 years.

Fortunately for the young, during peaceful times stories of past loss and pain have little place. Childhood’s purpose is to play, explore and learn.

As I walked back from Jakarta Two an anguna[4] stopped. Several boys disembarked, perhaps they were around 13 years old.

“Good afternoon,” I said.

“Good afternoon. Where are you going?” One enquired.

“I’m going to Ainaro.”

“Where have you come from”

“I’ve been praying at Jakarta Dois.”

“Praying?”

“Praying for the people who perished there.”

“Did people perish there?” he asked.

Though some of the young might be unaware, the legacy of those dark times is embedded in the landscape and marked by the relative absence of an older generation, those who might offer wise counsel.

[1] https://lists.riseup.net/www/arc/east-timor/2016-04/msg00096.html

[2] O God of spirits and of all flesh, Who hast trampled down death and overthrown evil, and given life to Your world, do You, the same Lord, give rest to the souls of Your departed sons/daughters,

Do you also Lord gather the souls of those who have died unnamed, those known only to you, those whose families might still grieve their loss, without knowledge of the deaths.

Keep them all in a place of brightness, a place of refreshment, a place of repose, where all sickness, sighing, and sorrow have fled away.

Pardon every transgression which they have committed, whether by word or deed or thought. For You are a good God and love humankind; because there is no one who lives yet does not sin, for You only are without sin, Your righteousness is to all eternity, and Your word is truth.

For You are the Resurrection, the Life, and the Repose of Your servants (names), who have fallen asleep, O Christ our God, and unto Thee we ascribe glory, together with Your Father, who is from everlasting, and Your all-holy, good, and life-creating Spirit, now and ever unto ages of ages. Amen.

[3] https://theconversation.com/travelling-with-timor-leste-57635

[4] Local public transport resembling a bemo.

Leave a comment